Tuesday, April 21, 2009

Introduction

Monday, April 20, 2009

Relationships in Spanish Film

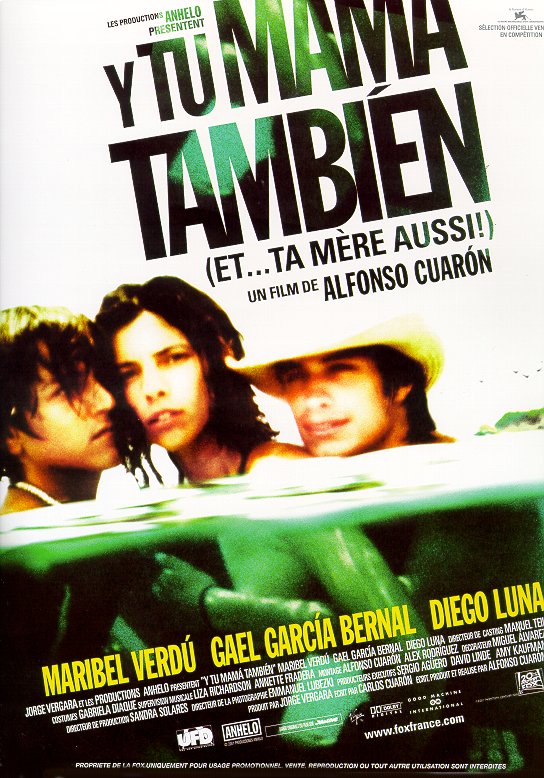

The Mexican film Y Tu Mamá También is a story of two teenage friends, Tenoch and Julio, who lose their girlfriends over the summer and go on vacation with Luisa, an older woman once married to Tenoch’s cousin. While on the trip Luisa, Tenoch, and Julio find themselves tangled in sexual relationships with each other. The climax in this movie occurs when Tenoch and Julio discover that they have each slept with the other’s girlfriend. The film involves several liberal views of relationships, most of which stray from the norm based on the age of the participants. The first instance of this in Y Tu Mamá También when the physical nature of Tenoch and Julio’s relationships with their girlfriends is revealed in the beginning of the film. Both couples are teenagers and are shown having sex right in the beginning of the film. Shortly after this, Julio is shown having sex with his girlfriend in her bedroom just seconds before her parents walk in. These two scenes stray from the conservative view that couples should not have intercourse until they get married, or at least until they are older, more mature, and better able to take care of themselves. The theme of sexual independence is present throughout the film as both Julio and Tenoch pursue Luisa. The relationship between these three also goes against typical conservative ideals. On the way to their vacation spot, “Heaven’s Beach”, Luisa ends up having sex with the two boys. The casual way Luisa has sex with both Tenoch and Julio also differs from the conservative view of sex.

Tenoch and Julio are both young teenagers and Luisa is an older attractive women who recently separated from her husband. To give a better understanding of the age differences, when Luisa was getting married, Tenoch and Julio were both around eight years old. It is not typical for people so far apart in age to become so close. Roger Ebert comments on the uses of sex in this film saying, “We feel a shock of recognition: This is what real people do and how they do it, sexually”. The liberal ways of life presented in Y Tu Mamá También are examples of how films are depicting a more liberal view than the older, more conservative Spanish culture. Charles Taylor of Salon’s statement in his review of the film points out the fact that “Erotic freedom has remained such an elusive ideal for movies that fresh, frank treatments of sex still have the power to shock us, to exhilarate us.” Here, he agrees that this film challenges the conservative norms of both his and many Spanish cultures. What happens in Y Tu Mamá También is perhaps an extreme case compared to the majority of Mexican and other Spanish language film, however it is by no means unfair to use the film when describing the progression of Mexican film. Charles Taylor describes its popularity saying, “Audiences in Mexico responded by making it the biggest hit in the country's history”. This popularity demonstrates the influence and respect it has gained and its legitimacy as being more than just a fringe movie. It also shows how filmmakers are getting comfortable challenging the social norms of what is and what is not acceptable.

Tenoch and Julio are both young teenagers and Luisa is an older attractive women who recently separated from her husband. To give a better understanding of the age differences, when Luisa was getting married, Tenoch and Julio were both around eight years old. It is not typical for people so far apart in age to become so close. Roger Ebert comments on the uses of sex in this film saying, “We feel a shock of recognition: This is what real people do and how they do it, sexually”. The liberal ways of life presented in Y Tu Mamá También are examples of how films are depicting a more liberal view than the older, more conservative Spanish culture. Charles Taylor of Salon’s statement in his review of the film points out the fact that “Erotic freedom has remained such an elusive ideal for movies that fresh, frank treatments of sex still have the power to shock us, to exhilarate us.” Here, he agrees that this film challenges the conservative norms of both his and many Spanish cultures. What happens in Y Tu Mamá También is perhaps an extreme case compared to the majority of Mexican and other Spanish language film, however it is by no means unfair to use the film when describing the progression of Mexican film. Charles Taylor describes its popularity saying, “Audiences in Mexico responded by making it the biggest hit in the country's history”. This popularity demonstrates the influence and respect it has gained and its legitimacy as being more than just a fringe movie. It also shows how filmmakers are getting comfortable challenging the social norms of what is and what is not acceptable.The Spanish-Argentine coproduction film, Elsa y Fred, is very different from Y Tu Mamá También, however it also incorporates liberal ideas that stray from typical conservative ideals of a relationship. Elsa y Fred focuses on Elsa, an elderly woman that still wants to live life, and Fred, an elderly man who’s wife recently died. Elsa is a very energetic and in some ways, immature, woman who, as Jean Oppenheimer describes, “has the conscience of a teenager who claims a death in the family in order to get out of a math test”. These neighbors first meet when Elsa backs her car into Fred’s daughter’s car. Eventually, they enter into a romantic relationship, living like many younger couples do.

They pull youthful stunts like running out on the check at an expensive restaurant and walking through a famous fountain in order to copy a famous scene from Elsa’s favorite movie. Elsa y Fred follows most of expected norms of their culture, following closely in line with the expectations of a relationship between two people. While this film is not nearly as liberal as Y Tu Mamá También, with its multitude of sex scenes, Elsa y Fred still challenges social norms with its focus on a relationship between two elderly people. The idea that two elderly people can act so youthful in their relationship and can find love again after losing a loved one, challenges the typical conservative way of thinking. Ruthe Stein agrees with this analysis, saying “Elsa & Fred raises a lot of questions about how to spend your senior years”. This challenge of social norms follows the theme that Spanish language films are depicting a more liberal view of Spanish culture. This liberal view is, in a way, depicted by Elsa and Fred’s children as they express their disapproval over their relationship. They disagree that they should be together and think the best thing to happen would be for the two to simply separate.

Both Elsa y Fred and Y Tu Mamá También include role reversals in the relationships where the women takes on a more dominant role in the relationship. This role change differs from the typical male focus seen in many early Spanish films and Spanish culture. In Y Tu Mamá También, the role reversal involves Luisa being the controlling person in her relationships with both Tenoch and Julio. She is the one who initiates the sex and comforts her two partners when they are feeling sad or inadequate. Philip French describes Luisa’s situation by saying “Along the way there is a gradual movement by which Luisa - first slowly, then suddenly - takes command of the party”. This analysis of Luisa’s role is correct. She plays the role of both the leading in the relationship and caretaker of the two boys when they begin to argue. Luisa was not always in the dominant position, as can be seen from her failed marriage. Luisa’s relationship with her past husband, however, is typical by conservative standards and Julio and Tenoch’s relationships with their girlfriends were also typical with them clearly playing the male role. This shows how Y Tu Mamá También incorporates both conservative and liberal views of Mexican culture.

In Elsa y Fred, Elsa also plays a dominant role in the relationship, although Fred still follows many of the typical roles he is expected to play. Elsa is the one who pursues Fred perhaps too rigorously while Fred, in the beginning, could care less and isn’t very interested in another relationship after the death of his previous wife. Throughout the movie Elsa is the one who constantly pesters Fred, whether its because she wants to go to a fountain in Rome or wants a cat. Her constant nagging and insistence on travel and items is more of the role most cultures would expect of her in the relationship. Her nagging of Fred shows her acknowledgment that she needs Fred's approval in order to get what she wants..

Recent Spanish film incorporates many liberal ideas about relationships that differ from older conservative Spanish ideas from their culture. The two films Y Tu Mamá También and Elsa y Fred both show this as they challenge conventional ideas of relationships in different ways. Y Tu También incorporates more liberal ideas of relationships by focusing on teenage sex, sex between people of different age, and a slight bit of bisexual tendencies in the two lead males. Elsa y Fred incorporate liberal ideas through its notion that elderly people can have just as interesting and energetic a relationship as young adults. Both films also challenge the notion that it is the male who is typically the stronger and more powerful one in the relationship and who should pursue the female. While Elsa y Fred is fairly conservative in its challenges of social norms and incorporates a relatively tame plot, the fact that even it displays some aspects of how Spanish language films show a liberalized view of their culture helps further the notion set forth by films like Y Tu Mama También.

French, Philip. "Macho Gracias." Rev. of Y Tu Mama Tambien. The Observer 14 Apr. 2002. Macho gracias | Film | The Observer. 21 Apr. 2009

Oppenheimer, Jean. "New York Movies - Elsa & Fred's Rancid Romance - page 1." New York News, Events, Restaurants, Music. 21 Apr. 2009

Stein, Ruthe. "Movie review: 'Elsa & Fred' - age is just a number." Rev. of Elsa y Fred. San Francisco Chronicle 18 July 2008, sec. E: E-5. Movie review: 'Elsa & Fred' - age is just a number. 21 Apr. 2009

Taylor, Charles. ""Y Tu Mama Tambien (And Your Mother, Too)" - Salon.com." Directory - Salon.com. 21 Apr. 2009

Ibero-American, Liberal Response to Chauvinism: Unachievable Justice

In Alea’s Fresa y Chocolate(1993), the Cuban issue of machismo is addressed mainly through the character development of David, a Cuban revolutionary. This dynamic character is primarily presented as a young man who adheres to the machismo attitude superficially but without full understanding or conviction. In the first scene, David brings his girlfriend into a run-down hotel room where he courteously tries to get her undressed after turning off the lights. His girlfriend, assuming that David simply wishes to use her, does not realize that he, under the influence of chauvinistic propaganda, might not know any other way to show his true love. After turning away from him, she turns toward the bedside light, saying, “All you wants is sex, like all men”.

With a better lit screen, her confrontation is seen in a more positive light than the dark and assumedly chauvinistic foreplay. Accordingly, David tells her that he can wait until they’re married and in a classy hotel to have sex. Here his own morals are better illuminated, or as Santi asserts, “David's moral hygiene [is] a fact established as early as the first scene”(15). From this point, the audience may begin to expect, or at least hope for David’s full transformation.

With a better lit screen, her confrontation is seen in a more positive light than the dark and assumedly chauvinistic foreplay. Accordingly, David tells her that he can wait until they’re married and in a classy hotel to have sex. Here his own morals are better illuminated, or as Santi asserts, “David's moral hygiene [is] a fact established as early as the first scene”(15). From this point, the audience may begin to expect, or at least hope for David’s full transformation. A greater challenge to David’s seemingly chauvinistic character appears in the next scene when he is joined by Diego, a seemingly flamboyant homosexual, at a table where he is eating ice cream. The flavors chosen by the characters are largely symbolic of their differing sexualities – David eats chocolate, while Diego eats strawberry. Although David is not a bigot at heart, in this scene he nonetheless harbors some feelings of prejudice against Diego. After all, “Diego is gay, religious and a nationalist, while David is straight, an atheist and a communist”(10-Santi). While David tries to ignore Diego, the camera maintains both on a horizontal plane.

Such an editing technique shows the deserved equality for both characters, that which David abstains from granting.

Such an editing technique shows the deserved equality for both characters, that which David abstains from granting. Even as David is roped into Diego’s life by his novel ideas, literature, and art, he still gathers information about Diego’s sacrilege against the state. Of course, Diego has his fair share of sabotage as he continually tries to seduce the young counterpart. However, as the characters spend more time together and confront one another about their differing beliefs, they start to feel guilty about undermining one another. Having learned much from Diego, David realizes that his own government is wrong to persecute people like Diego, but knows that nationalists will not be tolerated. Therefore, when Diego stands next to the wall of nationalist and communist trinkets, representative of their differing ideals, he challenges David with the question, “Someday I could say hello to you in public?” The answer known, David lowers his head.

On a personal level, both Diego and David have come so close to absolute reconciliation.

However, as the lighting in this scene suggests, they still have their differences. As Diego chooses to challenge the government, so exiling himself, David cannot convince himself to do the same. Near the end, Diego apologizes for trying to seduce David; and yet, David cannot bring himself to apologize for informing the Communists about Diego’s sacrileges. So as Santi says, “under the banner of a strong nationalism the film proposes the eventual reconciliation of the two political halves of the Cuban nation, torn asunder for almost four decades by the Communist regime.”(4), the keyword here is ‘eventual’. As a melodrama, the film vies for liberal acceptance and compassion, making headway through the intellectual transformation of a superficially chauvinist character; but in the end, justice for Diego does not triumph. Still, with so much of the movie revolving around Diego, and his gay, religious lifestyle, this Cuban film has a largely liberal tone. This melodrama therefore sends the message, that in response to chauvinism, ultimate liberal justice for the age of Cuban machismo is unfortunately unattainable.

However, as the lighting in this scene suggests, they still have their differences. As Diego chooses to challenge the government, so exiling himself, David cannot convince himself to do the same. Near the end, Diego apologizes for trying to seduce David; and yet, David cannot bring himself to apologize for informing the Communists about Diego’s sacrileges. So as Santi says, “under the banner of a strong nationalism the film proposes the eventual reconciliation of the two political halves of the Cuban nation, torn asunder for almost four decades by the Communist regime.”(4), the keyword here is ‘eventual’. As a melodrama, the film vies for liberal acceptance and compassion, making headway through the intellectual transformation of a superficially chauvinist character; but in the end, justice for Diego does not triumph. Still, with so much of the movie revolving around Diego, and his gay, religious lifestyle, this Cuban film has a largely liberal tone. This melodrama therefore sends the message, that in response to chauvinism, ultimate liberal justice for the age of Cuban machismo is unfortunately unattainable.In the Spanish film noir, La Mala Educación, the issue of chauvinistic behavior never completely resolves itself either. The story originates from the sexual abuse and manipulation of a boy named Ignacio by Monolo, a Catholic priest. Needing revenge, Ignacio does blackmail Monolo, but never finds his lost love, Enrique, from Catholic school. Thus, his life is not restored to what he dreamed it to be. By the time the audience meets him, the young Catholic boy has become a transvestite junkie. When the cost of drugs starts getting out of hand, Ignacio begins stealing money from his family. His brother, Juan (alias Angel), along with Monolo(who is now in a relationship with Juan) decide to kill him for demonstrating the same privileged identity that excused Monolo’s predatory actions under Franco’s fascist regime. However, before Ignacio dies, he leaves an autobiographical play that shapes his life a bit more continuously through fiction. In it, he is portrayed as a thieving homosexual whore, but one who eventually finds Enrique. Of course, Juan, having helped murder Ignacio, decides that his brother’s dream is still within mortal reach. He then proceeds to do all of the things Ignacio desired, both in real life and fiction. Not only does he take on a relationship with Monolo, for which he can achieve a later vengeance; he also meets the real Enrique and succeeds in having a relationship with him, as warped as it may be. Juan even acts out the role of Ignacio in his own idealist play. However, the film’s director, who happens to be the real Enrique, decides that all cannot go according to plan - Ignacio must die at the hands of Monolo. After acting out the altered last shot, Juan cannot help but sob. Now he can sympathize with his dead brother, for he realizes that perfection is unattainable.

Through the many twists and turns of its plot, this film noir adequately confuses the audience, logically and emotionally. The identities of the actors are so jumbled; even when everything comes together, the sense of the story still seems lost. Indeed, this is the feel characteristic of such liberally reactionary movies. When people realized that liberal justice could not always be achieved through vengeance or the state, they could likely sympathize with dissatisfied and alternative characters from the movie. After being subjected to the chauvinist motives of anyone from under Franco’s fascist Spain, people could not correct and restore all that had been brought into confusion. The advent of open homosexuality also served to befuddle those with absolutist definitions about sexuality. Such a fatalist, somber mood is achieved through the black and red mise-en-scène

, characteristic not only of vengeance, but also of film noir movies in general. (31 - LAM) The typical pessimism of film noir is also acknowledged through allusions to other noir movies in the background, as seen in the subway scene

, characteristic not only of vengeance, but also of film noir movies in general. (31 - LAM) The typical pessimism of film noir is also acknowledged through allusions to other noir movies in the background, as seen in the subway scene .

. In conclusion, both Fresa y Chocolate and La Mala Educación, with their liberal portrayals of sexual and religious activity, addressed the abusive machismo sentiment that dramatically affected Cuba under its revolutionist movement and Spain under Franco’s fascist rule. David, the initially chauvinist Cuban, approaches the ideal of homosexual acceptance by befriending the intellectual, nativist-gay, Diego. However, in the end, David does not equate himself entirely with Diego, letting him be exiled from the still intolerant Cuba. The omnipresent iniquity of ethics is highlighted by means of mise-en-scène, cinematography, plot, and editing. In La Mala Educación, all of the characters try to live out mimicked ideals of justice through vengeance; yet, as the mood suggests, unhappiness accompanies these failures. Ultimately, it is uncertain whether the films deny the earthly capacity for justice, or if they simply consider it beyond the scope of newly liberalized states.

Works Cited

Barsam, Richard. Looking At Movies: An Introduction to Film. Second Edition. W.W.

Norton and Company. New York, London.

“Fresa y Chocolate”. UC Santa Barbara Department of Spanish and Portuguese Language

Literature Culture Film.

La Mala educación (2004). Movie Gazette.

Santí, Enrico Mario. “FRESA Y CHOCOLATE: THE RHETORIC OF CUBAN

RECONCILIATION”. ICCAS Occasional Paper Series. May 2001.

Crime equals Fame

All countries in South America were colonized by Spain expect for Brazil, which was colonized by Portugal. These countries share another thing in common; they were all fighting for their independence in the mid to late nineteenth century. During this time period many “moviemakers” obtained their ideas from Spanish literature and plays. Only the greatest parts of their culture where produced for the big screen. As the iberamerican filmmakers realized that they had goals of reaching the international market, the ideas of the film market started to broaden. After wars of independence had been fought in the South American countries, filmmakers started producing films that showed honor in fighting for what one believes in. This liberalization of iberamerican film has continued to change the values and culture that are now being shown to the world. Brazil and Ecuador have seemed to be embracing andpossibly glorifying crime in their films in recent years. Is being a criminal the same as being a celebrity? Well by watching the City of God and Crónicas films, it appears that they are very close, if not the same thing.

According to Kevin Matthews, “Several participants in the panel discussion on Brazilian cinema disputed the notion that violence is a particularly prominent feature of contemporary Brazilian cinema.” This concern is shown very clearly in the film City of God. By using two brothers that must grow up in a dangerous neighborhood, the film shows how making a career choice can have a huge impact on your life. Everyone wants power or influence in his or her life to some degree. The only difference is that there are some people willing to do whatever it takes to gain the power.

City of God is a film that shows how powerful the culture in the ghettos or slums can be for a child growing up. The children in City of God do not have a choice but to accept the drugs and guns that are associated with everyday life. In the film, Rocket is the younger brother to Li'l Zé who is running a drug empire. Rocket has dreams of being a photographer, but in order to survive in the City of God he must succumb to certain things that are looked at as a part of everyday life. Rocket becomes friendly with a group that finds pleasure in smoking marijuana. This is seen as a crime in some countries, but in other countries or cultures, this is seen as a part of everyday life.One might be more or less influenced to smoke depending on the morals or legality of the issue, which differ from country to country. Another huge issue this film reveals is dealing drugs.By showing how much power and “fame” Li'l Zé has in this film, it is in a way glamorizing drug dealing. Is that good for the youth in this world? It is proven that the more a person is around a certain activity by seeing or hearing, the more they will tend to act in that manner. So, should filmmakers show how much power the king of a drug empire has, or should they focus more on the hardships of pursuing this sort of career? Mimesis and catharsis are the best examples of this argument. There has always been an on going argument of what and what should not be shown to society since the time of Greek philosophers (Looking At Movies). Does it or doesn’t it influence people? Maybe because that argument focuses more on the psychology of watching a film, it varies from person to person. City of God does make a point to show the danger also related to running a drug dealing empire, which helps to even out the good and bad in this film. Perhaps exaggerating these hardships a bit, in the middle of the film a once law-abiding citizen, Handsome Ned, seeks revenge because of the rape and beating of his girlfriend. Handsome Ned becomes involved with drugs, guns, and murder. Towards the end of the film there is another drug dealer shown being arrested. The crooked police humiliate Li’l Zé, but then let him off for an amount of money. In the end Li'l Zé is shot and killed by a gang that felt the need to gain revenge for a member of their gang that was killed by Li'l Zé. So no matter how much power Li'l Zé had, he died because of the path he chose to take.

A lot of the issues in this film explore how people’s morals are starting to become less important to them. This reporter was having such a power struggle that he committed a crime. It is illegal to hold evidence. Manolo believes that Vinicio is the murderer of all the children, but he is so busy trying to prove this himself that Vinicio get released from jail before the police find out that Manolo is holding evidence that could be used to prove that Vinicio is guilty. “An examination of journalistic ethics, the film explores the willingness of the media to surrender its morals for a shot at fame and profit”(themoviebox). The film also questions who the real criminal is,” the criminal, the media, or our society?”(themoviebox).

The South American countries, according to Gaberila Martinez, “to a greater or lesser degree these populations have intermingled, creating a racially and culturally diverse continent.” Even though it may be very diverse, Brazil and Ecuador seem to agree on crime. Both of these countries have liberalized their cinema by showing this part of their culture. Brazil even went as far to base City of God on a true story. These films also seemed to bring in more modern uses of editing and color techniques. This helps to show that iberamerican filmmakers are putting true effort into modernizing their works of art. While these movies may be liberalizing, they are also continuing to bring the traditional argument of mimesis and catharsis into their films, which may be said for almost all thiller/crime themed films. Other cultural aspects that both of these films hit on is the diversity of culture and beliefs that are shared in both societies. Both of these films do a great job of showing how their countries are beginning to liberalize. Before the independence wars were fought, only the best parts of culture were shown; however, today the tougher parts of culture are being brought to the surface in films. Through this and by using much more modern editing these iberamerican filmmakers are really reaching out to the rest of the world.

Works Cited

Barsam, Richard. Looking At Movies. 2nd ed. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2007.

"City of God." Department of New Media. U.

"Cronicas." TheMovieBox.net. Apr. 2009

Martinez, Gabriela. "Cinema Law in Latin America: Brazil, Peru and Columbia." Jump Cut. Apr. 2008

Matthews, Kevin. "Brazilian Cinema Reborn." UCLA International Institute. 02 Nov. 2005. Apr. 2009

Familism in Mexico and Brazil

Two nations that have, at one point in their history, had male dominated societies are Brazil and Mexico. The paternalistic influences from the past have been detrimental to family life, as evidenced by the proliferation of Machismo. As one might expect, people do not sit idly by when ruled by an oppressive force. The reaction to Machismo, colloquially known as Familism, is a shared value to both Brazilian and Mexican families. Familism embraces the idea that the family is of greater worth than self. Family members embracing Familism are willing to sacrifice their own happiness or even health for the benefit of those they love. One study has even found that, “[i]n many ways, the Hispanic family helps and supports its members to a degree far beyond that found in individualistically oriented Anglo families” (Ingoldsby 1991).

Through an analysis of La Misma Luna and Dois Filhos de Francisco, this paper will attempt to show that, even in the face of Globalism and Machismo, the influence placed on the importance of family remains strong in Mexican and Brazilian cultures.

One film that beautifully represents the importance of family in Mexican culture is La Misma Luna (Under the Same Moon). In this film, a mother (Rosario) and son (Carlos) have lived in different countries for the last four years – the Rosario in the US, Carlos in Mexico. Even though they have regular interaction, they long to be together; the film documents the son’s perilous journey across the border and eventually to Los Angeles and the arms of his mother. All along the way, the moviegoer witnesses the effect of Familism on the characters’ actions. The first example of this happens early in the film, when the son’s grandmother dies. The audience sees the boy – only 9 years old – taking care of his ailing grandmother by making her breakfast and doing other miscellaneous tasks for her. His actions stand is stark contrast to what would be expected of a young American boy in the same situation. He does not act out of a sense of duty, but rather he acts out of love.

A second example of Familism is apparent when Rosario considers marriage to legal US resident. She does not love the man, but appears willing to sacrifice the idea of romantic marriage just so that she can give her son the life she thinks he deserves. That is a true sacrifice that demonstrates how much she values her son’s happiness.

Even though the film celebrates the power of a unified family, it does not ignore other forces at play in Mexican family culture. Carlos’ father has been absent his entire life, which could be interpreted in two different ways. One possible interpretation of his absence is that he stands for the evils of the old paternalistic family structure and is best left out of the family. Another reading of the father’s absence could be that globalization has pulled the father away, and the western influences are an evil to be avoided. Perhaps the father is pursing the American Dream at the expense of his child. The film, however, only briefly touches on difficult issues. One reviewer notes that, “[t]he filmmakers know that middlebrow movie audiences prefer their thorny social issues served lite and with a side order of ham” (Catsoulis).

As reflected in the film Dois Filhos de Francisco (Two Sons of Francisco), Brazilian culture still holds strongly to many principles of Familism. Multiple scenes in the film show this and also offer some differences between Brazilian and Mexican Familism. The film covers the life of two boys, Mirosmar and Emival, who develop a love for music that will shape the rest of their lives; they develop this love thanks in-part to the urging of their father. Nurturing this love for music, however, causes many hardships for the family. As one might expect, the boys’ parents are willing to make the necessary personal sacrifices that will allow the boys to have a better future.

One scene that demonstrates the parents’ willingness to sacrifice personal happiness for the happiness of their children occurs when the mother of the boys, Helena, resigns herself to the idea that they must leave home at an early age to be successful. It is not easy for Helena to let go of her own plan for the boys, but she sacrifices time with them and control of their future so they can pursue their dream. This self-sacrifice is alignment with Familism values.

The family life of the boys in Two Sons of Francisco is very different from that of Carlos in Under the Same Moon. Where Carlos lives separated from his mother and estranged from his father, Mirosmar and Emival come from an unbroken family. One possible reading of this difference is that globalization of western family values has taken hold differently in different Latin American cultures. It is possible that the country of Mexico has been more influenced by the idea of pursuing the American Dream at the expense of family than Brazil has. It is interesting to note that Emival and Mirosmar come from the country in Brazil and are visible shaken when they are forced to move into the city at one point in the movie. Their shock could be interpreted as a Brazilian disinterest in many western ideals that ignore the importance of family.

Ingoldsby, B. (1991). "The Latin American Family: Familism vs. Machismo." Journal of Comparative Family Studies 22:57–61.